Policymaking in the Age of Absurdity

How can Albert Camus help us make sense of today's geopolitics?

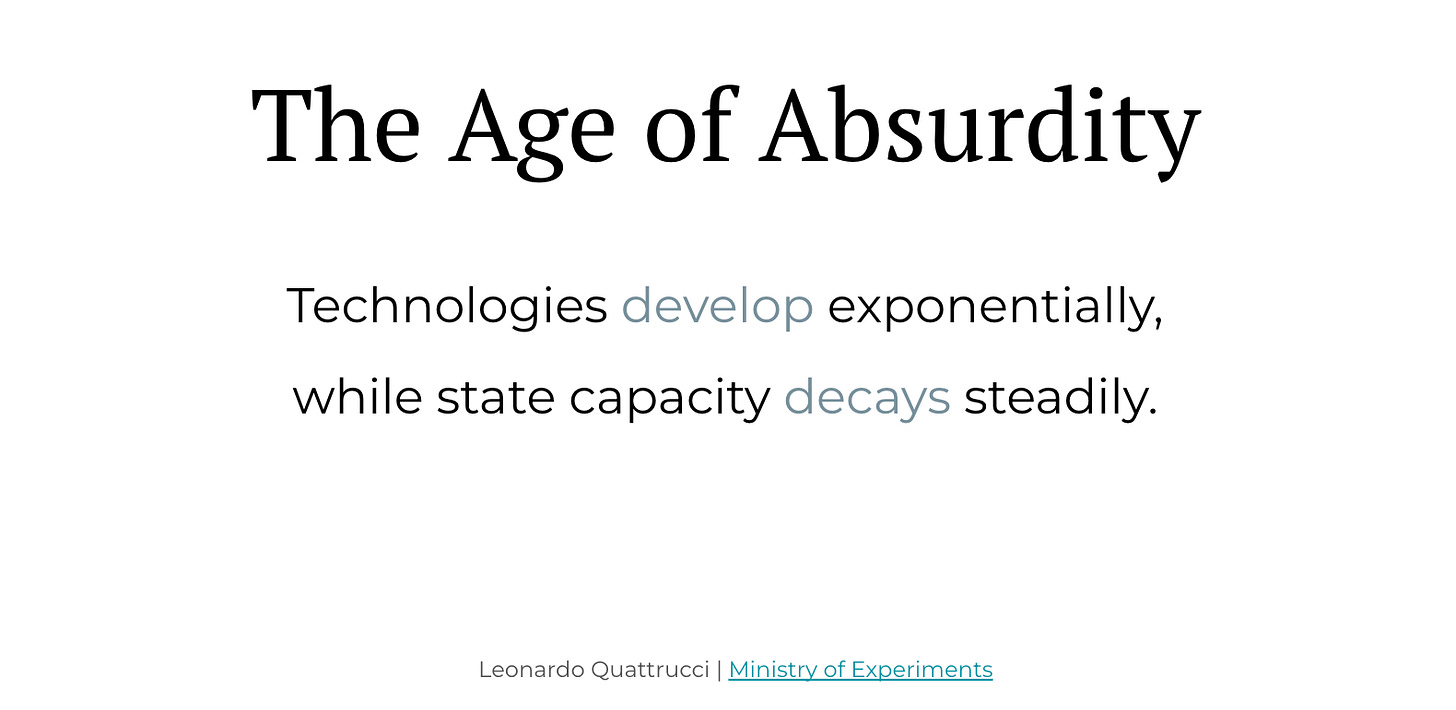

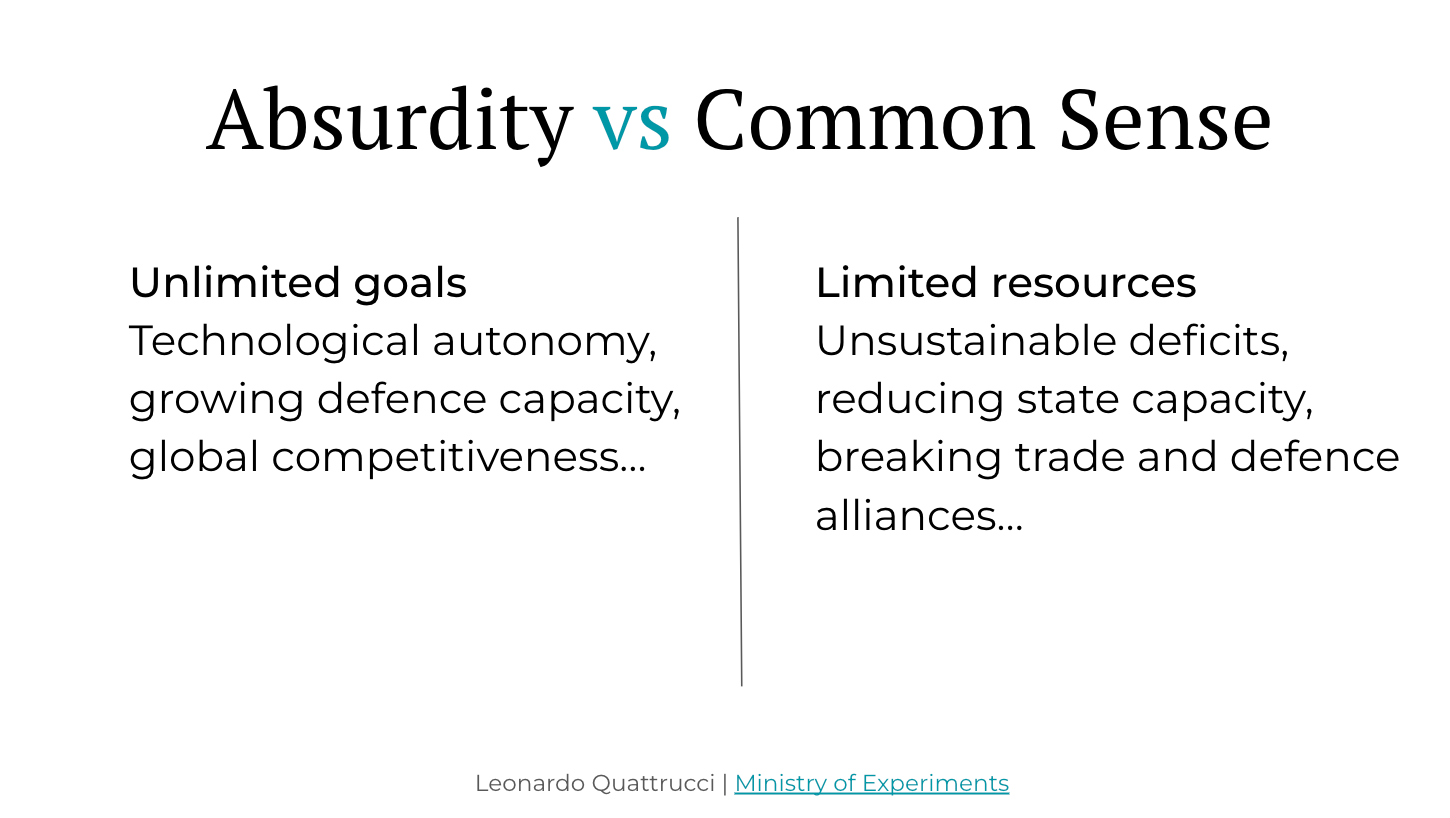

Our present can be defined as a conflict between absurdity and common sense.

Absurdity is a “divorce” between reasonable expectations and reality, to paraphrase Albert Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus. Would you ever expect a diplomatic conversation between two presidents to turn into televised drama?

Common sense means proportioning limited means with unlimited ends, in John Lewis Gaddis’ definition from On Grand Strategy.

The conflict centres around one paradox, the following:

On the one hand, Western governments are restoring Cold War-era ambitions: establishing superiority over adversaries through technology. Today, like in the 60s, geopolitical readiness is technological readiness, and vice versa. The ethos of the competitiveness agenda is the one prophecised by Vannevar Bush in his 1945 pamphlet, Science: The Endless Frontier:

“A nation which depends upon others for its new basic scientific knowledge will be slow in its industrial progress and weak in its competitive position in world trade, regardless of its mechanical skill”

On the other hand, these unlimited ambitions of autonomy and dominance clash against three (growing) limits.

1. Technology is made of complex networks

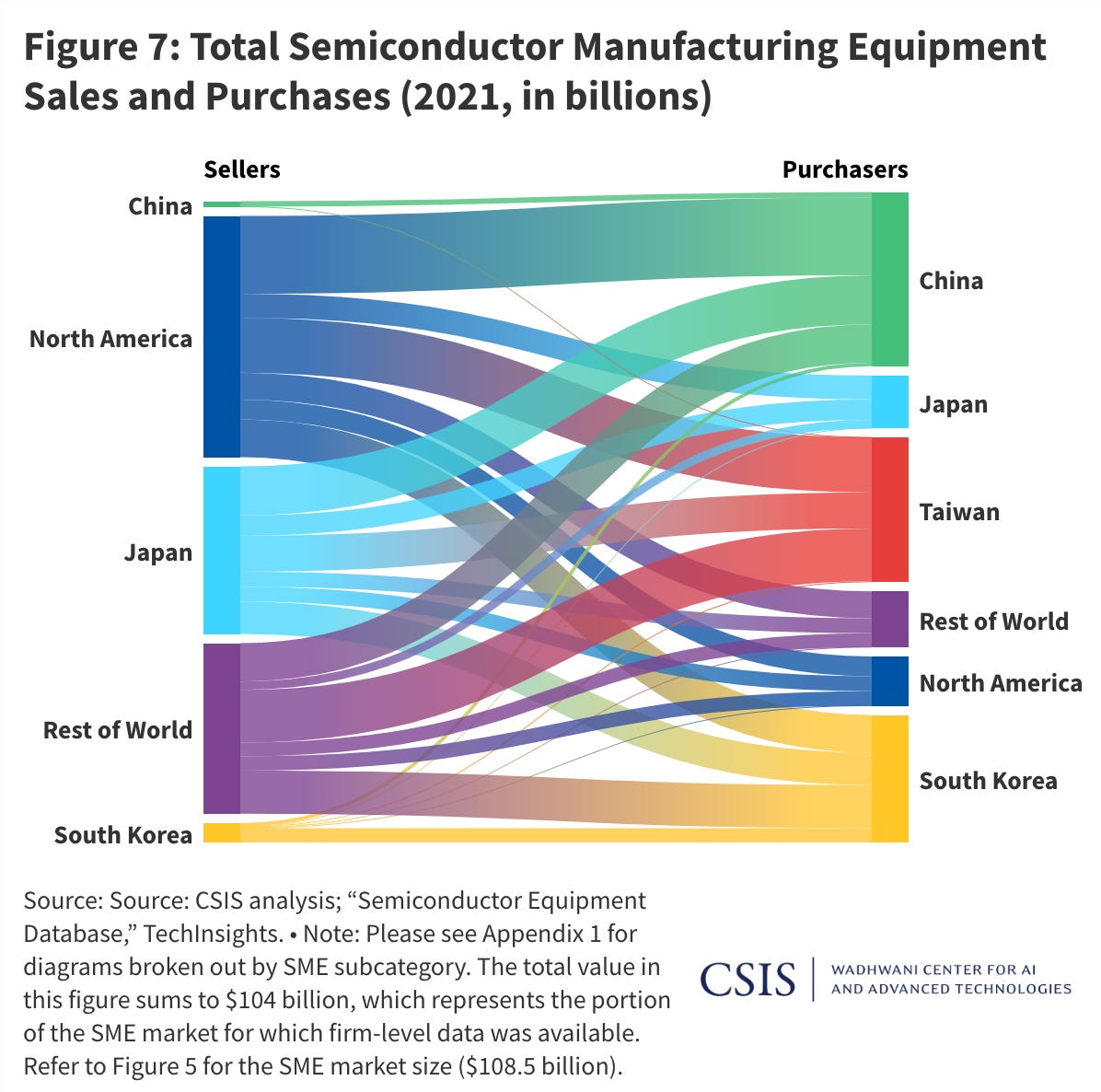

Today, “No country in the world alone can make an iPhone,” as Oxford University economist Eric Beinhocker put it. The statement is even more true for more complex technologies, such as semiconductors — as illustrated by the figure below from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

This is a direct result of 1960s policies, when the United States created hardware alliances with Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea to penetrate the Soviet sphere of influence. Today’s American policies intend to directly reverse these choices by bringing these manufacturing capabilities to American soil.

Emerging technologies critical to state interests, such as quantum, neurotechnologies, or biotechnologies, rely on even more complex supply chains of talent, technical, and natural resources.

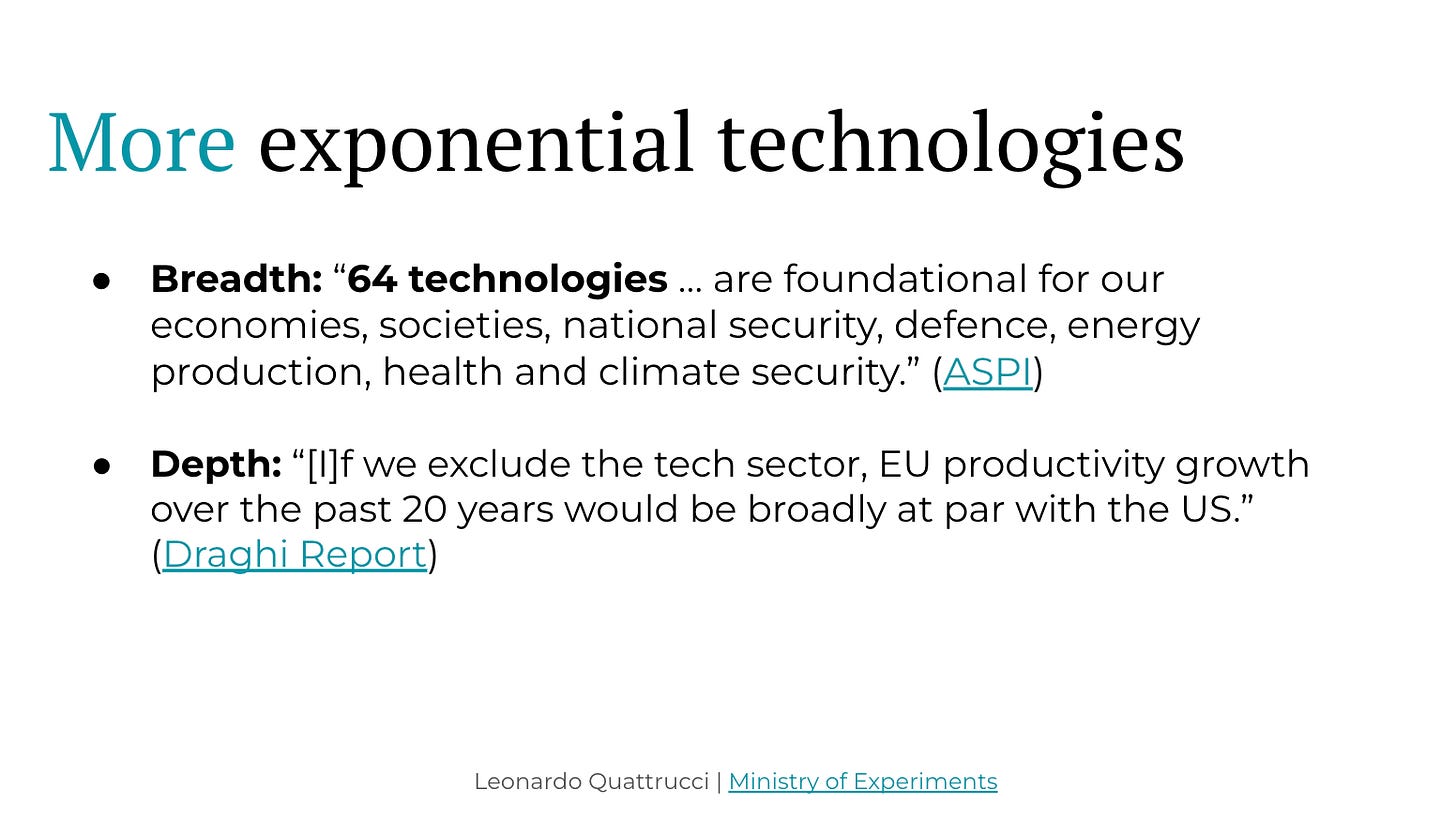

The portfolio of critical technologies is broader and deeper than in the 1960s. According to ASPI’s Critical Technologies Tracker, there are 64 critical technologies. How can one appropriate 64 critical technologies and develop them autonomously?

This objectively hard task is made even more challenging by a second limitation.

2. The world is breaking into spheres of influence, again

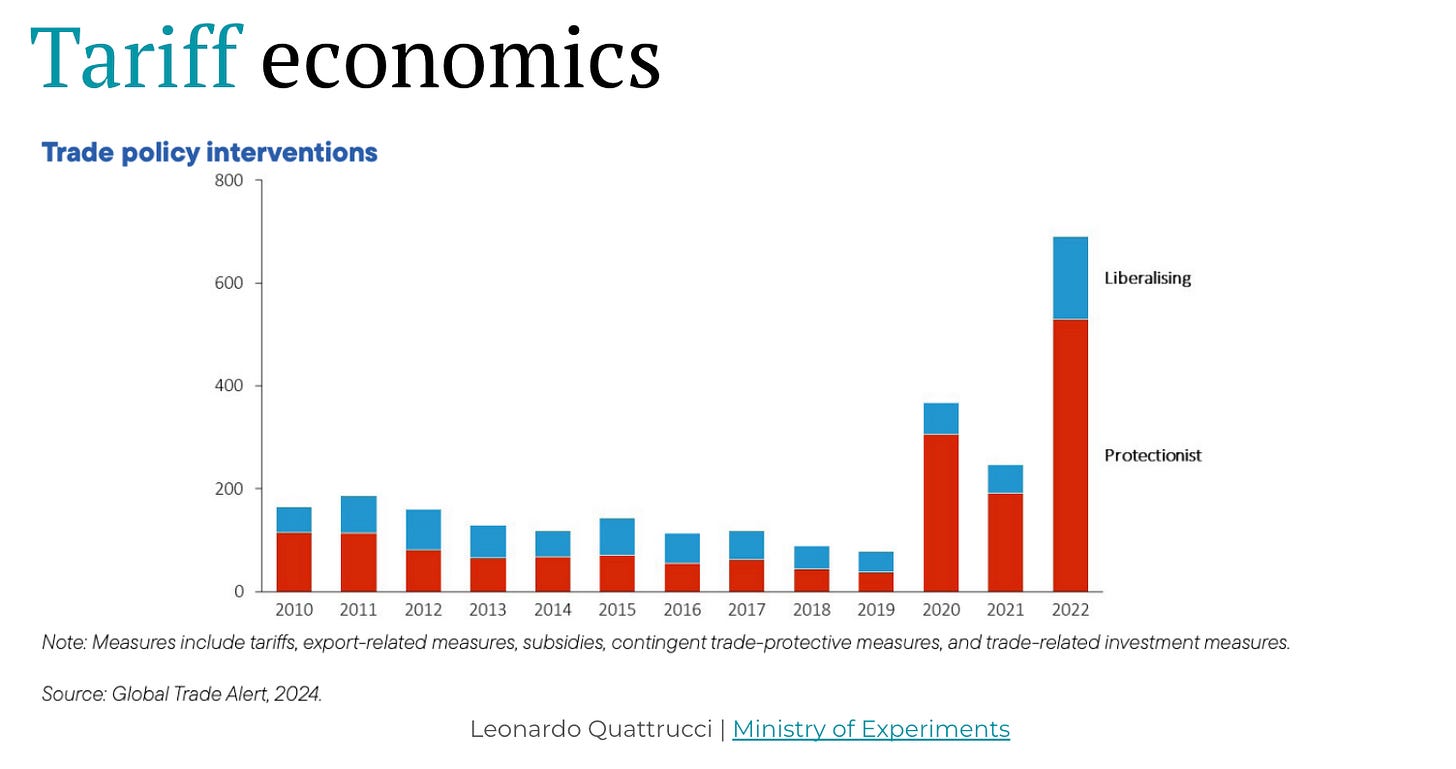

The appropriation of critical technologies by the States has a partner in crime: the policy of coercion. This is marked by the return of tariff economics," which as Ian Bremmer, President of the Eurasia Group, explains: “is not mere negotiating strategy, the goal this time is to replace a global rules-based system of managed economic integration with coerced decoupling.”

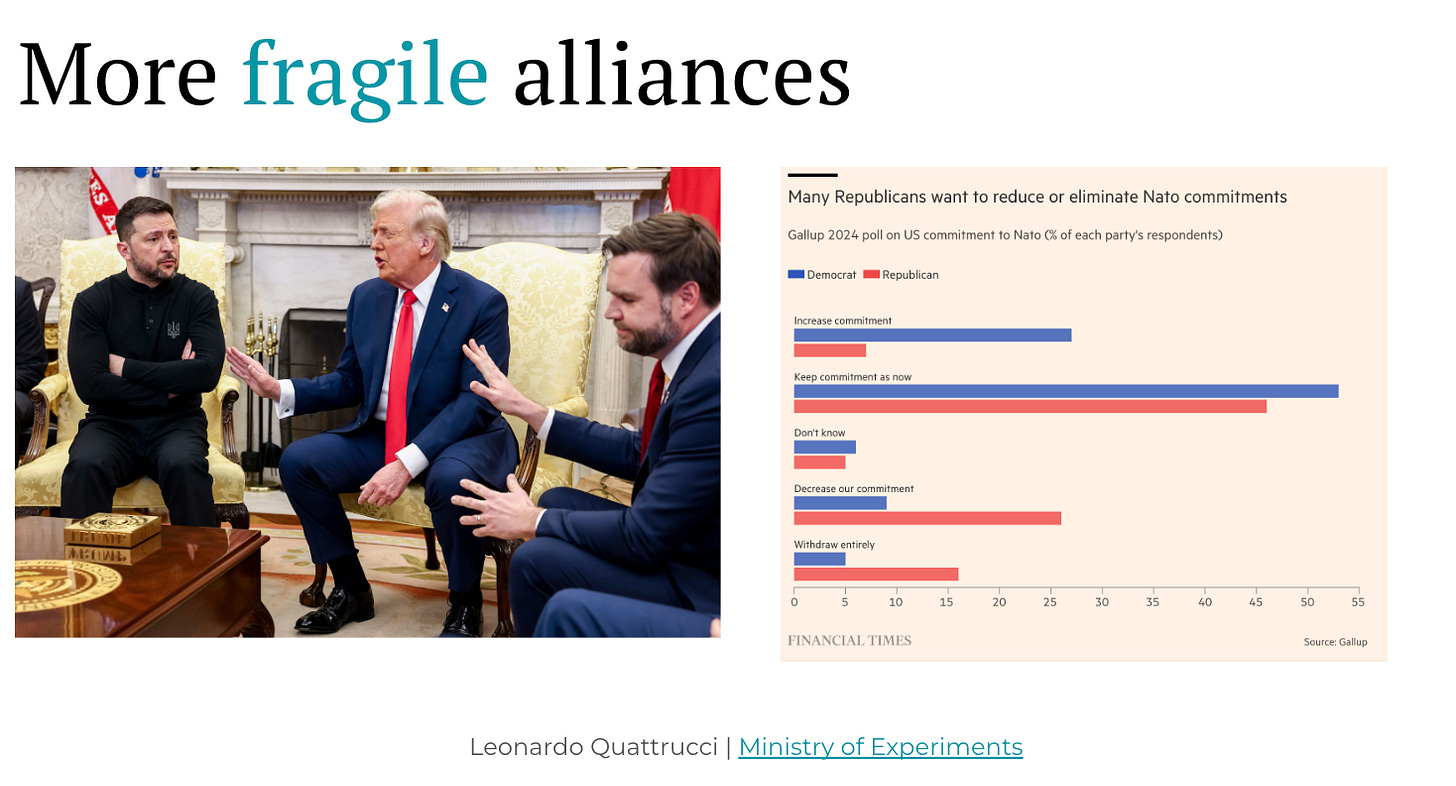

This trend does not make sense economically, but it does make sense in the age of absurdity because the logic driving States has changed. Old alliances have become more fragile because they are no longer based on shared values, but strenght.

In Trump World, strength trumps values. In the words of Professor Monica Duffy Toft: today, "regime type no longer appears to hinder a sense of shared interests. It is hard power only—and a return to the ancient principle that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

In this world, those who fail to embrace absurdity fail to adapt. Failure to adapt is likely to mean subjection to someone stronger. Whom? That is unclear because, as opposed to the Cold War, there will not be two spheres of influence emerging, but many more.

As established alliances like NATO become more fragile, new players gain space to affirm their interests in the geopolitical arena. For example, in the ASPI leaderboard of critical technologies, China is currently leading in 57 of 64 areas, India now ranks in the top 5 countries for 45 of 64 technologies. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have destined hundreds of billions to build sovereign AI and attract talent and unicorns, especially as conflicts destabilise other innovative hotspots like Israel.

While the supply chain of critical technologies is entrenched in global networks, the world is being sliced up into spheres of influence — again. There are more players ready to compete for power, compared to the past. While during the Cold War, the State shaped markets to sustain industrialization, now the vigour of governments is diminishing in many parts of the West. Often by design. That is the third limitation.

3. State capacity is decaying — by design

At the time of Vannevar Bush’s writing, the State had the force to affirm its strength. It created new industries, like semiconductors, by de-risking private investments in industries that had yet to be created.

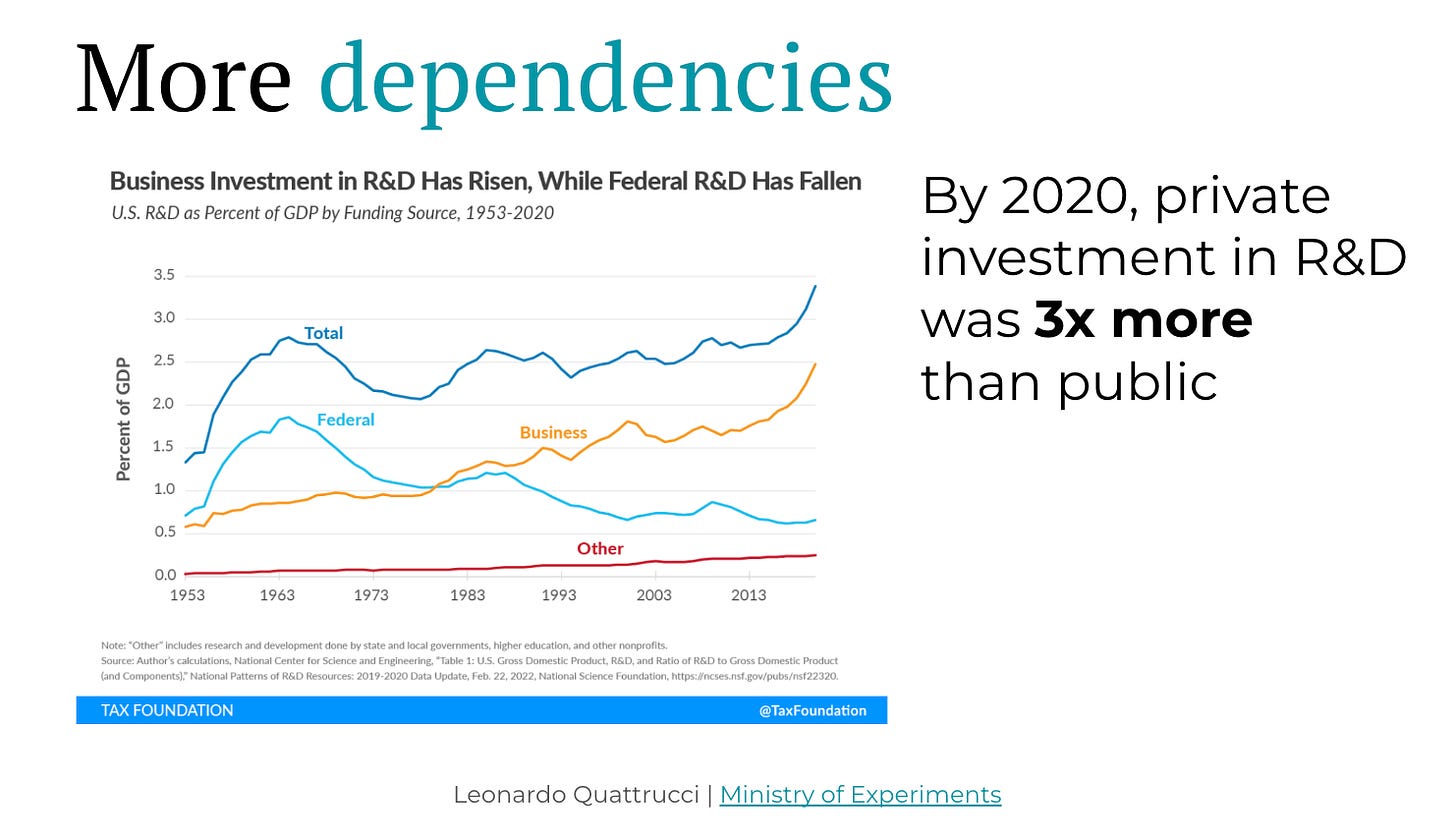

Now, the technologies critical to national interests, at least in the West, are owned, funded, and produced largely by private actors. Private investment in R&D has long surpassed its public equivalent—see below. Big Tech is to industrial policy what DoD was in the 1960s.

Notably, the dependencies of states on tech firms are now being internalised by the State. The Department of Government Efficiency has the explicit mission of minimising the government, which is a very different end goal from reforming it to its essential functions. Or to make it stronger without adding weight, as

would put it.To understand DOGE to date, I recommend reading 50 Thoughts on DOGE on

. But for the purposes of this talk — now essay — it suffices to remember that:“DOGE is using the right-leaning definition of ‘state capacity.’ But if you want Singapore-style effectiveness, you need to do some things that historically coded left, like paying civil servants more and giving them more freedom.”

I would argue that, today, DOGE is more of a dogma than a doctrine. Dogma is dangerous because its only form of consistency is rhetoric: The narrative does not have to be coherent, it can even contradict itself, so long as it sustains the belief in the dogma. This is why the culling of institutions will not stop, even though it seems to be fuelling recessionary trends in the US economy.

To be sure, the decay of institutional capacity is not Elon Musk’s doing — it had been taking place well before the creation of DOGE. Some essential government functions have long been poorly run, under-skilled, and left to obsolescence. For example, public procurement is essential to governments, it represents 12% of the OECD’s GDP, but it often poorly run, under-resourced, and bureuacatic to the point of absurdity. Similarly, AI is a stated priority by governments worldwide, but a survey by Apolitical shows that only 15% of civil servants receive training in the technology.

Institutions determine countries' prosperity. So, it is absurd that some governments aim to deliberately abolish them with little common sense, even as they seek to increase their competitiveness.

It is equally absurd that we had to wait for DOGE to show that systems can be changed and that our institutions are mostly inadequate for the 21st century.

So:

What does a proper Department of Government Effectiveness look like?

That should be the central question for policymakers in the age of absurdity. Common sense dictates that institutions must equip themselves with sufficient and proportionate means to achieve their ends.

When technological breakthroughs occur at increasing speed, institutions should be like good software: fluid, flexible, and ever-evolving. The core components of the system are skills, tools, data, and culture.

1. Governments should be free to acquire the right talent for the right job

Some basic institutional math reveals an impossible mismatch between aspirations and capabilities in most governments. With few exceptions, civil servants join governments at the peak of their skills, and that depletes over time because they have little incentives or no programs to upgrade their hard competencies.

During my time at Amazon, I learnt about the principle of bar-raising. At the company a candidate gets hired if that person raises the bar: is he or she better than the majority of her peers? This mechanism assesses competence and cultural fit and ensures that a new hire helps the overall business improve its capabilities.

How can governments be expected to manage emerging technologies without technologists?

More importantly, with the explosion of ubiquitous artificial intelligence foreseen for the coming years, execution and management capacity will become disproportionately important. Generative AI can already write a briefing or a communications plan that is on par, if not better, than a human. But decision-making and implementation will be differentiating capacities of leaders. Today, government has very few product or program managers, which are precisely the roles that make the most innovative public agencies like DARPA effective.

2. To manage innovation, governments must fix procurement

Governments’ problems with talent are also problems of procurement. If governments cannot readily buy and experiment with new tech, how can they be expected to manage it in the public interest?

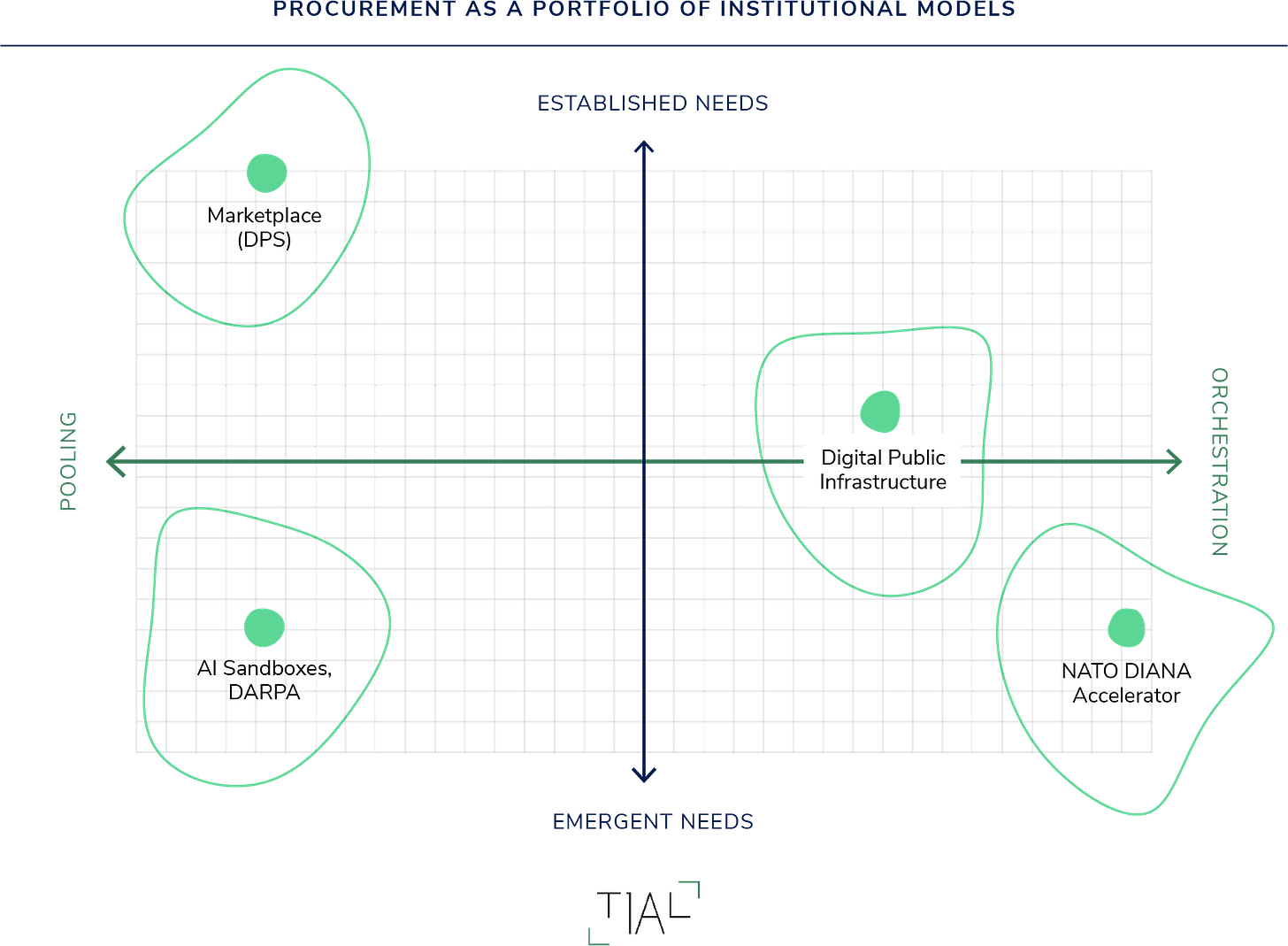

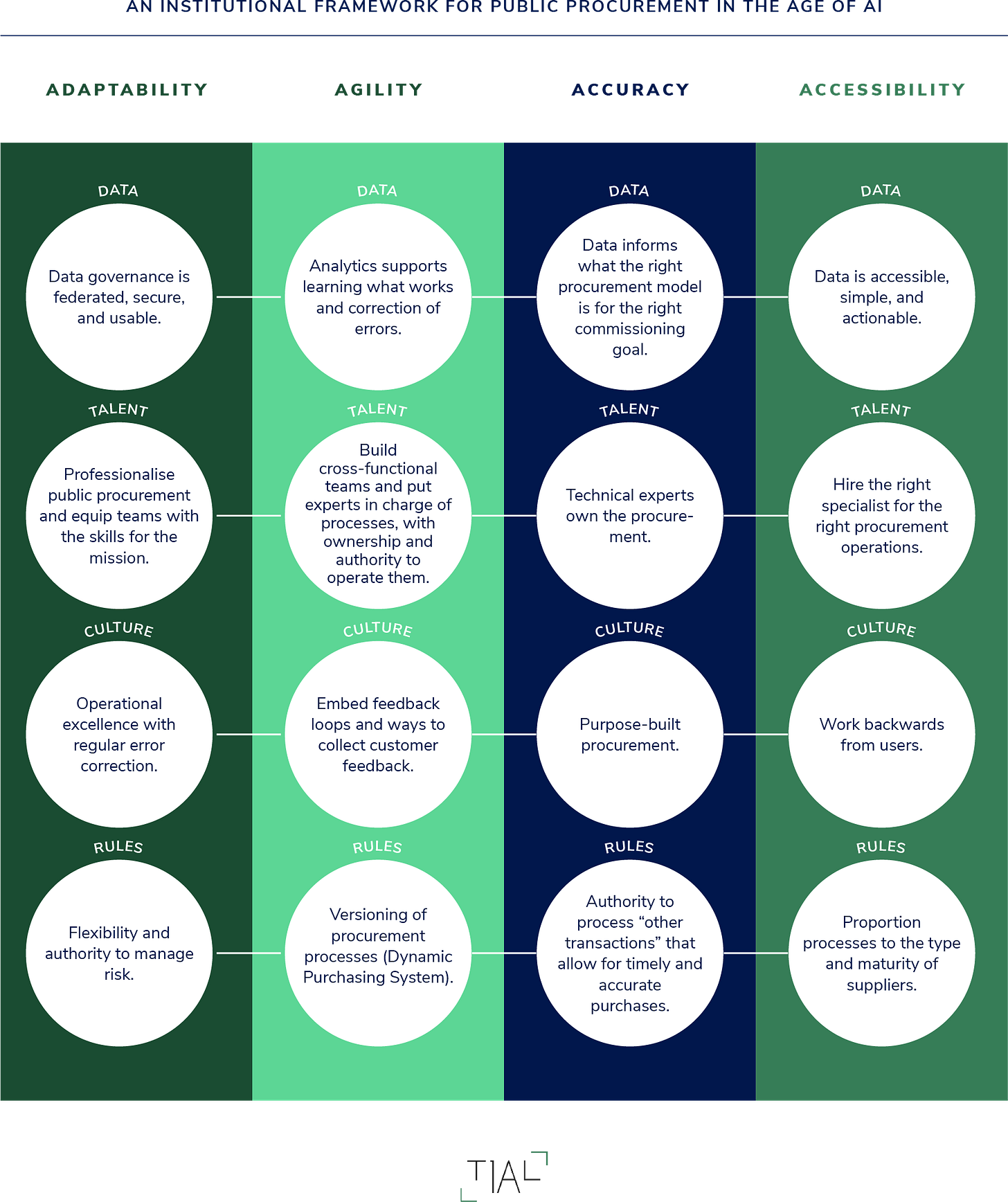

I propose a model for Well-Architected for Public Procurement in a paper I wrote for The Institutional Architecture Lab. I argue that procurement is the control tower of institutions: the operating system that allows them to proportion sufficient means to achieve their goals. Namely, common sense. The institutional upgrade of procurement capacity should follow four principles:

Adaptability: Procurement must shift from rigid rule-following to dynamic risk management, ensuring governments can continuously update their capabilities.

Agility: Instead of one-time purchases, procurement should be designed as an iterative process with feedback loops that refine and improve over time.

Accuracy: Procurement models should match the characteristics of what is being purchased. Buying cloud computing should not follow the same process as buying office furniture.

Accessibility: Procurement systems should be transparent, open, and navigable, reducing barriers for startups and new entrants while ensuring fair competition.

Following these principles would allow buying functions to be tailored to the nature of the product. It would turn public procurement into a strategic tool to shape markets and increase institutional competitiveness, rather than leaving it as a standardised shopping function.

3. Smarter governments need an intelligent data infrastructure

The CEO of an AI company that automates contract negotiation and management shared with me that, on average, 80% of the contracts in large governments are “unmanaged”. Meaning that they buy, say, a piece of software and then forget about it while continuing to pay for it.

I have argued with

that, to reap the benefits of AI, in terms of efficiency gains, prediction of needs and simplified negotiations, public institutions need to have a federated data environment. Large companies are already reaping these benefits, and there is no reason why the public sector could not do the same.An integrated, transparent, and accurate data infrastructure would allow public institutions to sit at the negotiation table with greater strength. Today, vendors tend to have more accurate data than buyers about their stock of purchases.

DOGE’s obsession with data and dashboards is well-placed and should be replicated.

4. Public-interest relentlessness

Rules, talent, and reforms without an innovative culture lead to compliance with absurdity and risk aversion. If there is one thing that a proper Department for Government Effectiveness should learn from the current DOGE, it is that the status quo is not inevitable; it is a choice.

In my personal experience, as a civil servant turned Amazonian, there is no reason why governments should not benefit from the same systems of operational excellence that make the most innovative companies in the world successful. With proper adjustments, of course, since hiring and firing the Federal Government as if it was Twitter is not only ethically questionable, btu also unwise.

That said, frequent objections to adapting corporate methods in the public sector are often questionable. Size, for example, is not an excuse: Amazon is several times larger than the European Commission. Huge scale inevitably brings some bureaucracy, but that does not stop Amazon from re-organising to maintain its competitive edge.

In fact, institutional reforms are only going to be reasonable and effective if they are systemic.

It would be common sense for institutions to cyclically assess their maturity to address their fundamental tasks and apply the necessary changes. Why?

Software that upgrades too slowly is outpaced by competitors, vulnerable to threats, and abandoned by users. The same can happen to institutions.

“I [reform], therefore we exist.”(Camus)

In the last few months, the logic of power has changed.

If we look at today’s politics from the perspective of yesterday, we would call our present absurd. In many ways, it is: many governments chase more ambitious goals while cutting their capacity. Nonsense, some would say.

This is, however, the new reality we live in: Absurdity must be taken seriously. In The Rebel, Camus built on his reflection on the absurd and argued that, to restore common sense in the interest of the “human community,” one has to first accept and then revolt to the absurd.

For policymakers, revolt should mean reform. Those who don’t adapt institutions will have to submit to world events that may not be very reasonable for a long while.

Welcome to the Age of Absurdity.

This essay is adapted from my talk on Policymaking in the Age of Absurdity at the GovTech Forum in Milan, on 14 March, 2025.

Bravo, nice article touching on a number of good points! One comment however, having recently moved to local govt after a long while in finance and tech I have to say the complexity of the task at hand is far greater than I’ve seen anywhere else in big and small business. The public accountability is stifling to the extreme and the talent pool and development opportunities are massively inadequate for the task at hand.